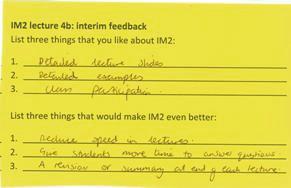

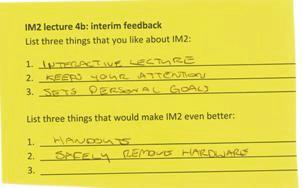

As is the case in most institutions, I am obliged to administer an evaluation questionnaire at the end of each course. It is a university-wide questionnaire which was developed so long ago that no-one can remember when! It includes 22 questions with Likert scales (e.g. “Enthusiastic about teaching the course”, “I understood the subject matter”, “Used OHP (and/or blackboard) well ”, “I would not go to this lecturer for help”) and a very small space for individual comments. A summary of the quantitative data is passed onto the head of our Teaching Committee (although it is seldom acted upon). I am given a quantitative summary as well as the original questionnaires, so that I can see the students’ comments. Most of the responses (quantitative and qualitative) raise issues that I am already aware of; for example, some students find the material difficult, some find it too easy; some students like class interaction, others don’t; some students like the assessed exercises, others don’t. I don’t find these questionniare responses particularly useful, and I am pleased that the university now has a working group with a remit that includes the production of a new university-wide questionnaire. But such end-of-course questionnaires are also ‘too late’ evaluation. While I may be able to improve the course for the following year, it is too late for me to make any changes which would affect these students’ experience. I therefore typically conduct an informal monitoring survey earlier on in the semester. I hand all students a coloured slip of paper (as shown) asking them for their comments, and give them approximately five minutes to complete it. (Aside: the use of coloured slips of paper makes them easier to collect!)

The comments are all summarised in a table of ‘likes’ and ‘suggestions’ for improvement, indicating the frequency with which each comment was made. I also include my own responses to the two questions (e.g. “...better if more students took part in class discussions”), and a few of the humorous student replies (e.g. “more Cake!”). This list is put on the class web page. At the next lecture, the most frequent suggestions for improvement are discussed openly with the class, and any changes to be implemented for the rest of the semester agreed on. This allows me to see if there are any serious problems that can be addressed immediately: in my most recent second year Information Management course, the feedback initiated a discussion on how best to give handouts to the class while still saving trees, and I was able to give evidence to the technicians at the students’ continued dissatisfaction with faulty technology in the lecture theatre. One of the most useful things about doing this is that students see what their peers think: those who hate in-class exercises can see that other students like them; those who want more examples discover that many students in the class think that the extent of examples is one of the best things in the class. I have found that this tends to reduce overall class dissatisfaction. Adding in some of the humorous responses and including my own list ensures that the students see this as a collaborative exercise (with me, not against me).

|